Lost To The Lake: The Wreck of the Carl D. Bradley

SS Carl D. Bradley

photo: University of Detroit Mercy Fr. Edward J. Dowling, S.J. Marine Historical Collection

In the 20th century, numerous ships called ‘lakers’ carried bulk cargo to the sixty-three commercial ports along the Great Lakes. Not only did these ships keep industrial centers supplied with iron ore, limestone, coal and grain, many of them were tragically lost to the lake. The most famous of these vessels is the SS Edmund Fitzgerald, which went down in 1975 in Lake Superior. Yet seventeen years earlier, the freighter SS Carl D. Bradley also sank in a November storm with an even greater loss of life.

Known as ‘Queen of the Lakes’, the Carl D. Bradley was the largest ship on the Great Lakes from 1927 to 1949. At 639 feet, it was the longest freighter on the Lakes until the launch of the SS Wilfred Sykes twenty-two years later. The largest self-unloading ship for its time, the Bradley was the Bradley Transportation Company’s flagship. Named after the president of Michigan Limestone, Carl David Bradley, this state of the art freighter had its maiden voyage in the summer of 1927. Since Michigan Limestone’s company base was in Rogers City, Michigan, the freighter drew most of its crew from this small community.

Because of its size, each year the Bradley served as an icebreaker through the Straits of Mackinac all the way to Indiana. The vessel’s main function however was to carry limestone to Lake Michigan’s deepwater ports from Lake Huron and Lake Superior. In 1957, the Bradley collided with the MV White Rose on the St. Clair River and underwent repairs to its hull. The following year, it ran aground twice, but never reported these incidents. The U.S. Coast Guard later speculated that the collision and groundings may have led to structural damage, and was thus a factor in the 1958 sinking of the ship. Since Bradley Transportation had never lost a ship since the founding of the company in 1912, the possibility of these events causing a disaster no doubt seemed remote.

Under normal conditions, the Bradley was the fleet’s busiest freighter. But due to efforts to unionize deck officers, 1958’s shipping season was delayed. Although the officers eventually voted down union representation, ships did not begin to go out until the end of April. The steel industry suffered that year, and the Bradley was decommissioned in July. Docked for most of the season in Rogers City’s Port of Calcite, the Bradley was only put back into service in October.

Carl D. Bradley unloading at a hopper at Michigan Limestone

photo: Presque Isle County Historical Museum

Just a few weeks later, the Bradley embarked on what was to be its last trip of the season. After delivering a cargo of crushed stone, the freighter left Gary, Indiana and headed to Manitowac, Wisconsin, where the vessel would be put into dry dock for the winter. The Bradley was but a few hours away from Manitowac when the company ordered them to the Port of Calcite for one more load of stone to deliver. On Monday, November 17, 1958, the steamer left Buffington, Indiana bound for Port of Calcite harbor in Rogers City, Michigan.

The Bradley’s captain was 52-year old Roland Bryan, a veteran seaman. Manned by a crew of thirty-five and carrying a light cargo, the Bradley headed out onto Lake Michigan at 9:30pm. But signs of severe weather were already in evidence when they left Buffington, where winds gusted at more than 35 miles an hour. It was the first ominous indications of an extreme cold front forming over the plains. Temperatures in Chicago plummeted twenty degrees in one day, and thirty tornadoes were sighted from Texas to Illinois.

Aware that gale winds were forecast, the crew readied the steamer for bad weather. They traveled along the Wisconsin shore until reaching Cana Island, where they shifted course for Lansing Shoal which lay across Lake Michigan. The winds on the lake reached 65 miles an hour by 4pm the following day. Still, the Bradley seemed to be weathering the gale force winds and heavy seas with little problem. This changed at 5:30pm when the Port of Calcite received a radio message from First Mate Elmer Fleming informing them that the Bradley, approx. twelve miles southwest of Gull Island, would arrive home at 2am. As soon as this message was sent however, a loud thud or bang was heard on the ship.

When the crew in the pilothouse saw the stern sagging, their next radio message was “Mayday!” With the ship quickly breaking apart, Captain Bryan gave the order to abandon ship. Power on the boat had already gone out. As the crew scrambled for the life rafts, the Bradley literally broke in two. As the stern sank to the bottom of the lake, there was an explosion as water flooded the boilers. Two lifeboats were kept in the stern, and a single life raft in the vessel’s bow. Given the speed of the disaster, the crew had difficulty launching the lifeboats, which became tangled in cables. The lone life raft flew clear of the sinking ship; four crewmembers swam through storm-tossed waves to reach it.

US Coast Guard Cutter Sundew

photo: Historical Collections of the Great Lakes - Bowling Green State University

Four miles away, the German cargo ship M/V Christian Sartori viewed the sinking of the Bradley. When they saw a burst of flames through their binoculars, the crew assumed the Bradley sank as a result of an explosion. The Sartori quickly headed to the Bradley, but it took them over ninety minutes to travel a distance of four miles. They were eventually forced to take shelter from the heavy wind and waves at Washington Island. Sixty miles away, the U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Sundew set out from Charlevoix in response to the mayday message. Due to the severe storm, the cutter didn’t even reach the area of the disaster until 10:40pm, five hours after the Bradley went down. Once there, rough seas prevented the Sundew from continuing their search. A second Coast Guard Cutter Hollyhock arrived at 1:30am from Sturgeon, Wisconsin. Such was the brute force of the storm on Lake Michigan that the captain of the Hollyhock described their seven-hour trip from Sturgeon as “a visit to hell”.

At 8:37am on November 19, the cutter came alongside the life raft that held surviving crewmembers First Mate Elmer Fleming and Watchman Frank Mays. The men were encrusted with ice and immobilized from the extreme cold. Swaddled in blankets, Fleming and Mays were brought aboard the cutter and carefully fed beef broth every thirty minutes. But they refused to leave the area while the search for their friends was going on.

Four crewmen had initially clambered onto the life raft. Twenty-one year old Gary Strzelecki was still alive when taken aboard the cutter, but died soon after. The fourth crewman on the raft, Dennis Meredith, had already perished. The twenty-five year old Meredith was barefoot when he got onto the raft, and clothed only in a sweatshirt and pants. Exposed for hours on the seas during such a terrible November storm, his odds of surviving were slim from the outset. By noon, the Hollyhock had begun to recover bodies. The cutter arrived in Charlevoix with survivors Fleming, Mays, and eight bodies. Later that night, the Hollyhock brought nine more bodies.

Since the Coast Guard cutters were expected to bring any survivors to Charlevoix first, friends and family members gathered there to keep vigil. They waited on the beach all night, directing their car headlights at the lake. With the return of so many bodies and only two survivors, the town seemed shocked into silence. In the days ahead, the search for survivors continued on the sea, air and ground, but the remaining fifteen crewmembers of the Bradley were never found. The search for the wreck itself had to wait until the ice thawed in the spring of 1959. The U.S. Corps of Army Engineers found the remains of the Bradley via sonar. The wreck lay approx. 360 feet below the surface of Lake Michigan south of Gull Island, and ¼ mile northwest of Boulder Reef.

US Coast Guard Cutter Hollyhock

photo: Historical Collections of the Great Lakes - Bowling Green State University

But the sonar readings did not answer the question of why the Bradley went down, nor did it confirm the surviving crewmembers’ statements that they had seen the ship break in two. Controversy ensued over the investigation. The Coast Guard claimed that the Bradley sank from what is known as ‘hogging’, a term which denotes the drooping of a ship’s bow and stern. Since ‘hogging’ causes stress to the hull, the assumption was that it contributed to the loss of the Bradley. Other theories included the ship’s metal fatigue when assaulted with a Great Lakes tidal wave, and the poor judgment of Captain Bryan, who headed out on the open lake in such a storm.

These theories were disputed by Coast Guard Vice-Admiral A.C. Richmond who pointed out that the ship had twice run aground in 1958; both incidents went unreported. There was also evidence of hairline cracks. In addition, the cargo hold was to undergo maintenance later that winter. All of which led to his conclusion that the ship went down as a result of an “undetected structural weakness or defect.” This conclusion appears to be bolstered by Captain Bryan’s own beliefs expressed in a letter he wrote shortly before the Bradley’s last trip. He complained that the Bradley was not as structurally sound as it should be and that he didn’t think it should be out on the lake in severe weather. Indeed he wrote of his relief that his ship was scheduled for a cargo hold overhaul.

Finally, like many ships built prior to 1948, the Bradley was constructed from notch-sensitive, brittle steel. This type of material was recognized as a factor leading to structural defects. The similarly constructed SS Daniel J. Morrell went down in 1966, the SS Edward Y. Townsend in 1968. The Coast Guard was advised to undertake structural overhauls on pre-1948 vessels. Following the loss of the Bradley, open life rafts were removed from Great Lakes ships and replaced with inflatables that came with protective canopies. Other safety changes associated with life vests, flares and rafts were also recommended.

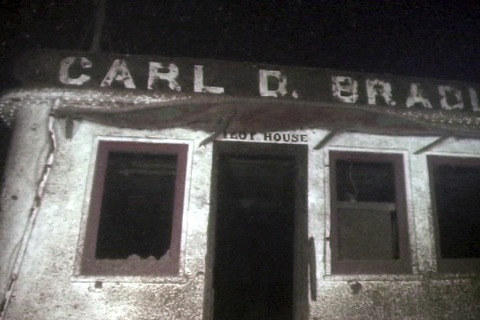

Pilot House of the Carl D. Bradley at the bottom of Lake Michigan

photo: Deep6-John Scoles/John Janzen

Not until 1997 were survivors Frank Mays and Elmer Fleming vindicated. Their claim that the Bradley broke in two was confirmed when marine explorers and authors Fred Shannon and Jim Clary went down in a submersible to view the wreck of the Carl D. Bradley. Accompanying them was survivor Frank Mays who once again gazed upon the hull of the Bradley nearly 40 years after it sank. What they saw was two upright pieces of the vessel, approx. 90 feet apart. The midsections were buried in the lake bottom’s mud, but the stern and remarkably undamaged bow were not. No one could now question Fleming and Mays’ long-time assertion that the Bradley went down in two pieces

Mass funeral for nine crewmembers of the Carl D. Bradley

photo: anonymous

The condition of the vessel is of little comfort to the families and friends of the lost Bradley’s crew. Thirty-three men died that November day, and twenty-three of them hailed from Rogers City, Michigan. As a town of what was then less than 4000 residents, the sinking of the Bradley had a devastating effect. Every street found itself holding a funeral, and fifty-three children were orphaned. During the memorial service for the crew of the Bradley, Great Lakes ships dropped anchor at noon in tribute.

Recovered ship's bell of the Carl D. Bradley

photo: anonymous

A memorial dedicated to the 43 men who died on the Bradley and the Cedarville (a Rogers City vessel that went down in 1965) stands in Rogers City’s Lakeside Park. The Bradley’s bell was recovered from the wreck and returned to Rogers City for a ceremony held on the 49th anniversary of the tragedy. The Carl D. Bradley tragedy was later featured in Andrew Kantner’s 2006 book Black November, and in the 2008 award-winning documentary November Requiem. Like many ships before and after her, the fate of the Bradley showed that not even the ‘Queen of the Lakes’ could withstand the storms of November.

Sharon Pisacreta (June 2013)

Carl D. Bradley

photo: University of Detroit Mercy Fr. Edward J. Dowling, S.J. Marine Historical Collection

Resources for the Carl D. Bradley:

Michael Schumacher, Wreck of the Carl D.

Andrew Kantar, Black November: The Carl D. Bradley Tragedy

Mark L. Thompson, Graveyard of the Lakes

William Ratigan, Great Lakes Shipwrecks and Survivals

Frank Mays, Pat Stayer, Jim Stayer and Tim Juhl, If We Make It 'til Daylight : The Story of Frank Mays

Lake Freighter at Wikipedia.org

SS Carl D. Bradley at Wikipedia.org

Steamer Carl D. Bradley site maintained by the Presque Isle County Historical Museum

Carl D. Bradley page on the BoatNerd website

Storms of Yore: Great gales on the Great Lakes at The Graphic website

Great dive photos of the Carl D. Bradley at Advanced Diver Magazine website

The official Marine Board of Investigation report on the foundering of the Carl D. Bradley on the US Coast Guard website