Lighting The Lake:

Crisp Point Lighthouse and Life-Saving Station

The Southeastern coast of Lake Superior from Munising to Whitefish Point was considered by sailors as “The Shipwreck Coast” during the 19th century. Many violent storms, thick white fogs or high winds affected many ships, some of which were pushed onto the shoreline. Many of these vessels trying to make Whitefish Point ended up foundering or wrecked. In answer, the government decided to establish five Life-Saving stations in 1875.

The Board of Life-Saving Officers chose Grand Marais, Muskallonge Lake, also known as Deer Park, Two Heart River, Vermilion Point and what is now called Crisp Point, fourteen miles west of Whitefish Point. It took another year before the stations were built and staff appointed to operate them in 1876.

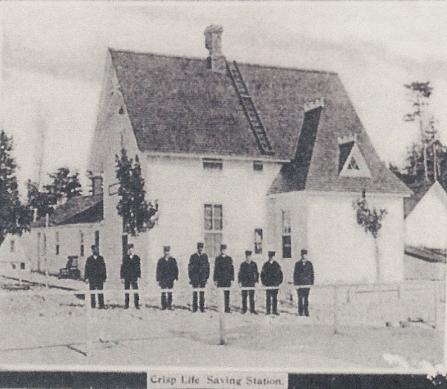

Crisp Point - Life Saving Station No. 10photo: US Coast Guard Archive

Here’s a short list of some of the disasters along that coastline:

- June, 1858—iron ore ship Indiana foundered

- November, 1864—steamer City of Cleveland went aground

- November 1869—schooner W.W. Arnold wrecked

- May, 1870—schooner Southwest went aground

- June, 1877—two ships collide

- October 1877—passenger steamer St. Mary blown out of water

- October, 1886—schooner Eureka capsized, six men lost

- June, 1887—steamer Argonaut foundered

- September, 1887—iron ore schooner Niagara tow line broken, nine or ten men lost

- May, 1891—coal schooner Atlanta sinks, five men and one woman lost

- September, 1891—schooner Frank Perew sinks, six men lost

David Grummond served at Station No. 10 between 1877 and 1878. He chose to leave and an “iron-willed” boatman Christopher Crisp was appointed to replace him. Crisp was originally from Liverpool, England, having emigrated to the States in early 1847. Crisp and his wife Gertrude, a Canadian, had five sons, two of which were born at the Life-Saving station. Gertrude died in 1888, however, when the youngest son was seven. Captain Christopher Crisp was considered the station’s first official Keeper-in-Charge and was paid an annual salary of $200. Surfmen serving at the station were paid $40 per month during the shipping season. Crisp was discharged as keeper on March 18, 1890, he was so well-known that the area was called “Crisp’s Point.”

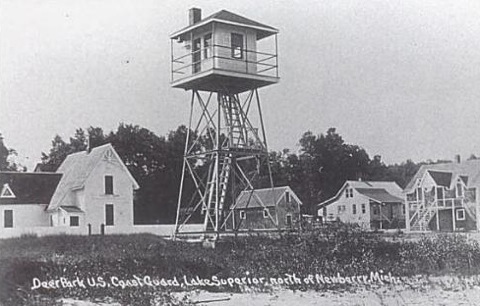

Deer Park lookout tower - similar to Crisp Point

The crew of the station performed duties beyond keeping a lookout for stranded or foundering ships. On June 18th of 1899 the steamer Germanic, with the schooner Emma C. Hutchinson in tow, both became stranded about 4 1/2 miles west of the station. Crews from Crisps Point and the Two Heart River stations boarded the Germanic and shifted 25 tons of iron ore from the forward to the aft part of the vessel which allowed her to back off the shallows. They then rigged a line from the Germanic to the Hutchinson and the steamer was able to pull her free. Heavy labor was often called for during service at the station.

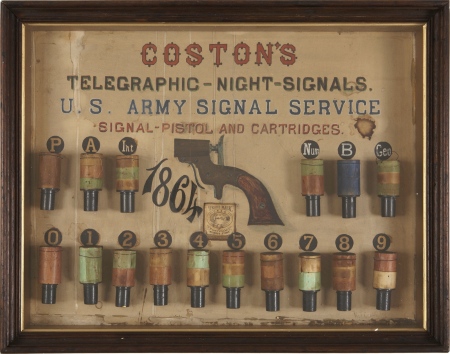

Coston Night Signals

Life at Station No. 10 included many instances of lookouts spotting ships heading perilously for the shore. On those occasions the station crew would show a Coston light signal to warn the ship and, in most cases, the ship would change course or back away. The Coston signal was an early form of flare gun in which the flare never left the gun, but produced a shower of colored sparks for approximately 8 seconds from the end of the barrel. A code was developed using different color cartridges that allowed communication similar to semaphore flags but visible at night or in light fog. Eventually it became apparent that a permanent solution for warning ships away from the coast was necessary.

In 1896, a lighthouse was proposed to be built at Life-Saving station No. 10, but was not approved until June, 1902. The government bought fifteen acres for $30 in May of 1903. Congress appropriated $18,000 to construct the lighthouse. In 1903, the fog signal building was erected but a storm destroyed the boiler. Once the second fog signal was installed, the standard whistle was changed to a chime. From 1903 until 1904, the 58 foot lighthouse and keeper’s dwelling were constructed of ironwork, brick and concrete. The light first became operational on May 5th of 1904 with a fourth-order Fresnel lens with a fixed red light, which could be seen 15 miles over Lake Superior’s waters.

Crisp Point lighthouse

Crisp Point’s first lighthouse keeper was John E. Smith, who oversaw First Assistant William J. Gramer and Second Assistant Charles H. Basel. Since the docks were destroyed in a storm, workers returned to install 750 feet of concrete walkways in 1906, which connected the station and the 132-foot stone-filled wooden landing crib in 1907. That year proved interesting – the keepers shoveled coal, almost 24 tons, into the boilers for 383 hours long to fuel the whistles. That was a station record, too.

But even with a lighthouse and life-saving station, the Great Lakes storm of 1913 claimed more victims from several ships. The fixed red light changed to a fixed white in April of 1924, with a new incandescent oil vapor system. An electric-powered air siren replaced the coal-fueled fog signal in 1933. Waves continually pounded the beach, which eroded the timber piers again and again in front of the station.

Many people on land were also helped by the crew at Crisp Point. A man from Ohio, Lou Williams, was found wandering in the sparsely populated woods and would have certainly perished had he not been found by the staff of the Crisp Point Station. In gratitude he wrote a poem:

CRISP POINT WATCH IS EVER

Roll Superior, cast thy strength; twisting, raging, turning.

But the Sailor knows no doubt or fear,

For through the night comes a glean of cheer - Crisp Point light is burning.

Rage Superior, spread thy fog, sleet, rain, and snowing.

But the Sailor sleeps in faith secure,

Though the stars are gone, the way is sure - Crisp Point horn is blowing.

Storm Superior, rage and roll. Spread thy vain endeavor.

Here no tale of death to tell - Crisp Point watch is ever.

Seal of the US Light House Service

The last keeper, Joseph Singleton, retired in 1939 when the Coast Guard took charge of the entire U.S. navigational aids system. They wanted to reduce costs and automate lighthouses. Electrification came to Crisp Point in 1941, but the Coast Guard boarded up the station and de-activated the light in 1947 due to radio and radar technological advances. They also demolished the deteriorating keepers’ dwelling in 1965, leaving the tower and attached service room. Lake Superior still defied modern technology – in November of 1975, the S.S. Edmund Fitzgerald sank during a storm only 17 miles northeast of Crisp Point.

The Coast Guard held an auction in 1997 for anyone interested in taking over care of the station. The Crisp Point Lighthouse Preservation Society was chartered by Ohio visitors Don and Nellie Ross, along with several area residents, to restore what was left of the station. Erosion to the collapsed service room and tower was halted with one thousand cubic yards of stone, laid around the tower’s foundation, and trees were also planted. In 1999 the Society cleaned and painted the tower and built wooden walkways. Crisp Point restoration served as proof that the 2000 National Historic Lighthouse Preservation Act is a worth-while cause.

In 2013, the Society plans to install a working light in the lantern room of Crisp Point Lighthouse . They have raised necessary funds to purchase the equipment. Donations exceeded the amount hoped for, and the organization hopes to light the lantern in May.

(Meg Mims, June 2013)

RESOURCES

Crisp Point Lighthouse at Terry Pepper's Seeing The Light website

Crisp Point Lighthouse at Wikipedia

Crisp Point Light Historical Society

Crisp Point Lighthouse at the Michigan Lighthouse Conservancy website

Great Lakes Lighthouse Tales