Lost To The Lake: The Disappearance of the Alpena

Wreck of the Steamer Alpena

drawing: unknown

The first steamboats were launched on the Great Lakes around 1816. Steamboat travel on the Lakes didn’t become widely popular however until the 1850s when railroads used them to connect with railheads. From that point on, steamboats were the preferred method of transportation for both lakeshore passengers and cargo. Unfortunately, the Great Lakes are not always the safest method of travel.

Case in point, the ill-fated steamer Alpena. Torn apart in what was called “the worst gale in Lake Michigan recorded history”, the Alpena remains one of the most famous lost ships of the Great Lakes.

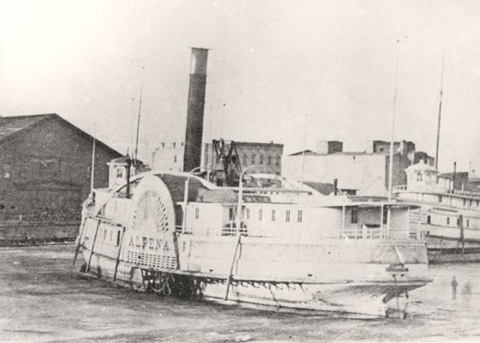

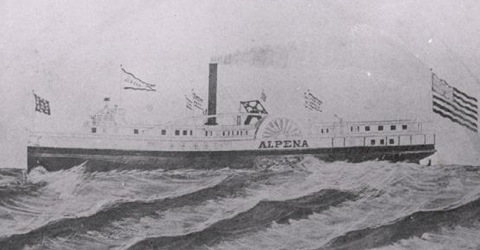

Built by Gallagher & Co. in 1866 at Marine City, Michigan, the Alpena was a side-wheel steamer measuring 197 feet in length. She boasted a wooden hull and a single cylinder engine that powered two side-wheels twenty-four feet in circumference. The steamer’s most striking features were the enormous paddlewheels, as well as the vertical beam engine visible above them. Indeed it was these two design features that led to her being identified after she went down in Lake Michigan.

photo: Fr. Edward J. Dowling, S.J. Marine Historical Collection

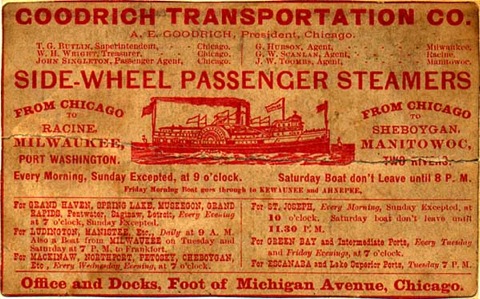

In 1868, the Alpena was purchased by the Goodrich line and later overhauled in Wisconsin in 1875-1876. Her new captain was the respected Nelson W. Napier, who hailed from St. Joseph, Michigan. For the next four years, the Alpena did journeyman duty on the Great Lakes with no major incidents until 1880. Tragically that was the year when she had the bad fortune to be out on the lake during a storm so powerful it became known as ‘The Big Blow’.

photo: Wisconsin Electronic Reader

Any sailor on the Great Lakes can testify that the waters and the weather can change almost instantly. And Lake Michigan is the most unpredictable. More major shipping disasters have occurred on Lake Michigan than on all the other Great Lakes combined. Still, both passengers and crew had no cause for alarm when the Alpena set out on October 15, 1880. It was perfect Indian summer weather: calm and sunny, with temperatures ranging from 60 to 70 degrees. By nightfall, this would all change.

After a stop at Muskegon, the Alpena continued on to Grand Haven where she picked up additional passengers and a cargo of apples. Bound for Chicago, she left Grand Haven at around 10pm with approximately 80 passengers and a crew of 22. Once underway, the previously gentle winds shifted, along with the barometric pressure. This indicated a storm was brewing out on the lake. The veteran Captain Napier took note of the change, but assumed he would reach Chicago before the worst of the storm hit.

Other ships sighted the Alpena that night as she continued on her 108-mile trip to Chicago. And although the sea was no longer calm, the Alpena did not initially appear to be in any trouble. Then a storm struck at approximately 3am. The Indian summer weather vanished as the temperature dropped below zero. Gale winds battered the lake, along with snow and ice. The dramatic change in weather was felt even in Chicago, where snow squalls hammered the city.

photo: Fr. Edward J. Dowling, S.J. Marine Historical Collection

The storm, soon to be dubbed ‘The Big Blow’, raged until morning. A barge and a schooner both reported seeing the Alpena struggling in the storm-tossed waves near dawn. At that point, she was about 35 miles off the shore of Kenosha, Wisconsin. The next sightings of the Alpena revealed a capsized ship, one of her massive paddle wheels sticking out of the water. Because she was stowing a large cargo of apples on her main deck, it is possible that the apples played a role in unbalancing the ship and causing it to capsize.

Not only did the Alpena sink during these hours, over ninety other vessels on the lake were wrecked or sustained serious damage. Pilot Island’s lighthouse keeper claimed that the waters of Lake Michigan remained white for a week, a result of the limestone on the lake bottom being churned up and smashed by the cyclonic winds.

Following the storm, the winds shifted west and northwest. The wrecked ship no doubt drifted back towards the west coast of Michigan where her journey began. For three days after the storm, there was no sign of the steamer. Then word spread that debris from the ship had drifted ashore near Holland, Michigan.

Horrifying evidence of the ship’s loss soon followed. The Alpena had been torn apart so furiously, bodies and wreckage were found along at least seventy miles of beaches. Indisputable proof of the Alpena’s loss came with the recovery of wreckage with the ship’s name on it -- along with thousands of apples bobbing in the water. Remarkably, a handwritten note tucked into a portion of a cabin washed ashore as well. Water soaked and barely decipherable, the note read: “This is terrible. The steamer is breaking up fast. I am aboard from Grand Haven to Chicago.”

Wreckage continued to wash up for the next forty-four years. Several recovered artifacts from the Alpena are on display at Holland Museum. As for the exact loss of life, that number is still disputed. Most historians estimate there were 80 to 100 people on board that night, with no survivors.

Although her final resting place remains unknown, there are sailors who swear that the passenger steamer can still be seen drifting through the mists on occasion. But whether she is regarded as a famous shipwreck or yet another ghost ship, the Alpena remains a Great Lakes legend.

---Sharon Pisacreta, © August 2012

drawing: Fr. Edward J. Dowling, S.J. Marine Historical Collection

Resources for The Alpena:

William Ratigan, Great Lakes Shipwrecks & Survivals

Alpena Goes Missing on the Michigan Shipwreck Research Associates website

Great Lakes Maritime History: History of the Great Lakes, Vol. 1 by J.B. Mansfield Published Chicago: J.H. Beers & Co. 1899

‘Alpena continues to haunt Lake Michigan’ by Jay Joslyn, The Milwaukee Sentinel, Monday October 20, 1980

Fr. Edward J. Dowling, S.J. Marine Historical Collection