Lost to the Lake:

The Seabird Disaster

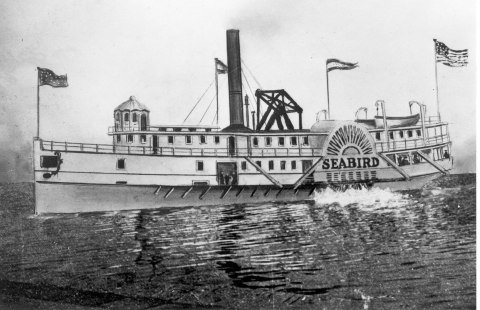

The Seabird

photo: The Independent

Although wild storms and rough waters claim the lion’s share of the lost ships on the Great Lakes, sometimes it takes just one careless mistake to send the crew and passengers heading into disaster. Such was the tragic end of the 19th century passenger steamship Seabird.

Built by E.B. Ward in 1859 at the Ward Shipyard in Newport, Michigan, the Seabird was a sidewheel steamer constructed of oak, with a hull measuring over 200 feet in length. [Author’s note: Although the ship was referred to as the Sea Bird in the 19th century, modern references spell the vessel’s name as one word.] She boasted two decks: one carrying freight and the other designated for passengers. Passenger cabins were placed on the hurricane deck. The forward deck staterooms were for gentleman, the aft reserved for women and families. Each cabin deck held fifty staterooms with two bunks per room; this allowed the Seabird to carry approximately 200 passengers on each trip.

The Seabird

image: OhioLINK Digital Resource Commons

After construction was completed, the Seabird arrived in Detroit where area newspapers noted: “This new and beautiful steamer, built by Captain Ward expressly for the Cleveland and Buffalo Route leaves for Buffalo this evening…The Boats charge $2.50 cabin and $1.50 steerage, which is half the Railroad fare.” However, despite the announcement of a permanent Cleveland-Buffalo route, by October of that year it had been discontinued without explanation. The Seabird was then transferred, along with her captain, C.C. Blodgett, to a route spanning Cleveland, Detroit and Lake Superior.

The 1860 and 1861 shipping seasons saw the Seabird experiencing several accidents on the water. The worst occurred as she traveled through the Straits of Mackinac where the ship caught fire. Fortunately Captain Blodgett’s quick thinking averted disaster and he had the fire extinguished without any passengers being aware of the danger.

Albert E. Goodrich

photo: quebecoise at FindAGrave.com

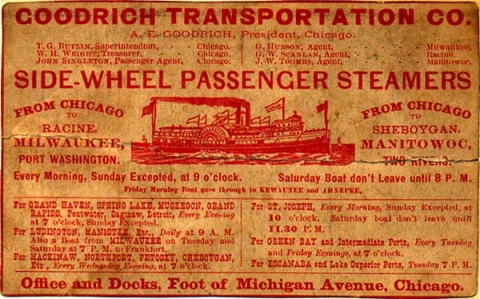

On April 21, 1863 Captain Albert E. Goodrich of the Goodrich Steamboat Line purchased the Seabird from E.B. Ward. Paying $36,000 for the four-year old steamer, Goodrich initially planned to use her on a regular cross-lake trip between Muskegon and Chicago but subsequently had to discontinue the Muskegon route due to dangerous sand bar conditions. The Seabird was transferred to the west shore route, which encompassed Lake Michigan stops in Chicago, Racine, Milwaukee, and Green Bay as well as various ports in Lake Superior. And from now until her destruction in 1868, the Seabird would spend the winter in Manitowoc.

The popular steamer suffered several mishaps in 1867, necessitating an extensive overhaul during the winter. Repaired and repainted, the Seabird would now be captained by John Morris, a highly regarded seaman. Accounts differ as to the number of crew members, but estimates range from 17 to 25, including a bartender, two cooks and a porter. One crew member was chief engineer Thomas Hannahan, whose wife begged him not to ship out after she had a premonition of disaster. Sadly, Hannahan ignored her warning.

One week before the Seabird departed Manitowoc for the 1868 season, a fire broke out in the Joseph Mann Factory’s paint shop. Everything burned save for several freshly painted tubs, which were then loaded onto the Seabird for delivery to Chicago.

photo: Wisconsin Electronic Reader

By Wednesday April 8, 1868, the Seabird had already completed three trips to Chicago, and was returning to Manitowoc to pick up a half load cargo of flour, tobacco, hardware, turnips and furniture. Some reports maintain that 35 passengers boarded at Manitowoc, nine of them children. She left port at noon with expected stops at Sheboygan, Milwaukee, Racine and Chicago. The day began with mild weather and the waters of Lake Michigan calm. A spring squall suddenly developed however, and the steamer didn’t arrive in Sheboygen until 3pm.

After taking on more passengers, the Seabird continued to experience rough seas to Milwaukee. Over one hundred people were now on board; out of that number 8 to 10 were women, and eight were children. She arrived hours late, and with many passengers suffering from seasickness. Several passengers disembarked here, unwilling to continue traveling on the stormy lake. Ever changeable, Lake Michigan had calmed down by the time the Seabird left Milwaukee around 11pm. Most passengers on board had retired for the night when the steamer stopped briefly in Racine to pick up cargo. The Seabird left Racine around 1:30am. Her final scheduled stop was Chicago the following morning, but the Seabird would never steam into harbor again.

postcard: oldmilwaukee.net

The next people to encounter the steamer were the captain and crew of the schooner Cornelia who conducted rescue operations. And at 6:30am, people onshore near Waukegan, Illinois reported watching a ship on fire several miles out to sea. As for what occurred actually on the Seabird, we must rely on the eyewitness accounts of the only survivors: businessman Albert C. Chamberlain and 22-year old Edmund Hennebury.

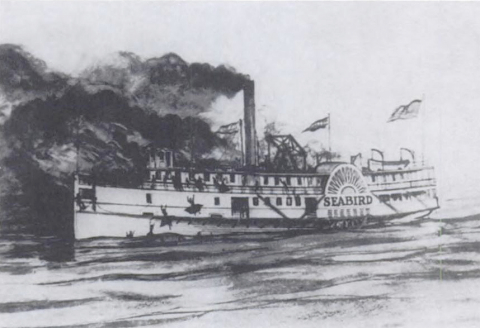

Although Hennebury was a sailor, he was traveling as a passenger. According to his statement, he awoke at 5am Thursday morning. Ninety minutes later, he observed smoke coming from the port section, main deck and the area beneath the ladies’ cabins. Almost as soon as he saw the smoke, a fire began blazing, undoubtedly fed by the tubs covered with straw in that area. Hennebury’s cries of ‘Fire!” alerted the crew, but within five minutes, the blaze had spread through the freight on the main deck and the overhead ladies’ quarters.

Chaos broke out on board as passengers rushed to the bow of the steamer. A half-dozen men, including Hennebury, threw the gangplank overboard. Hennebury jumped into the water after it, followed by ten to fifteen others. It was imperative to get onto the gangplank as quickly as possible since the lake was so cold; most people could survive only four or five minutes in such temperatures. While many of these men struggled to hold onto the gangplank, only Hennebury succeeded. He remained standing on the gangplank, balancing himself by gripping the plank ropes with fingers that quickly became frozen.

image: unknown

Dozens of passengers drowned in the heavy swell about him. Although they tried to cling to boxes and chairs floating on the water, the sea was very heavy, and the water temperature near freezing. Those remaining on board tied themselves to the ship’s doors, boxes and tables. With the sea drowning out any cries or screams, he watched as the Seabird burned almost to the water edge. Hennebury managed to stay balanced on the plank over four hours until he was rescued by a small boat sent out from the Cornelia.

The other survivor account comes from Chamberlain. Startled awake at 6:30am by loud cries and knocks, he recounted how the entire upper deck of the ship was ablaze in minutes. The lower decks were blanketed with smoke. According to Chamberlain, “ Everything was confusion. The passengers were rushing forward, the ladies and children crying and weeping. They all seemed powerless to aid themselves or others. The men rushed around frantically, looking for some means to save themselves.”

After putting on a life preserver, Chamberlain was astonished that most passengers did not do the same. Unlike Hennebury, Chamberlain remained onboard the entire time, lashing himself to the flagpole. He was stunned to see the Seabird’s captain calmly standing among the chaos, doing and saying nothing.

As the fire raged, many threw themselves overboard. But the steamer was at least six miles from shore making it unlikely that anyone would survive the near freezing waters of the storm tossed lake. Indeed Chamberlain saw many corpses still clinging to the floating wreckage. Forty-five minutes after the fire began, only Chamberlain and one other man still remained on board. Soon the fire consumed the small ledge the other man clung to, forcing him into the water where he soon drowned.

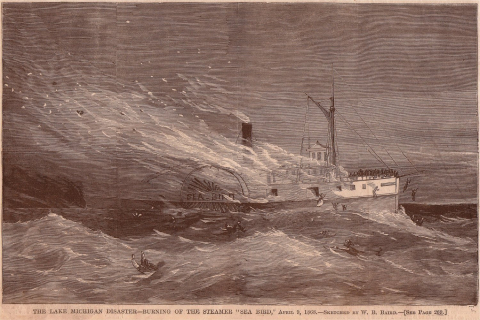

woodcut original: Harper's Illustrated Weekly

When Chamberlain saw the rescue schooner, he waved his cap until they sent out a boat for him. Once the Cornelia had picked him up, Chamberlain told them he had earlier seen a man floating on the gangplank. The rescue boat consequently caught sight of Henneberry about a mile away and rescued him as well.

There were later reports of a third survivor. James H. Leonard claimed to have survived by clinging to a section of the paddlewheel box for twelve hours until he washed ashore ten miles north of Evanston. However some newspapers remained skeptical of his story, even though people in Leonard’s hometown vouched for his honesty.

As to the cause of the terrible fire, both Chamberlain and Henneberry reported that people onboard claim a porter was seen throwing two buckets of live coals overboard right before the fire started. Tragically, the porter did not heed the old sailor warning about not throwing against the wind. As soon as he flung the coals over the side, the blustery northeast wind blew them back onto the ship where a large combustible cargo lay waiting.

It is very likely that the cargo that initially caught fire were the freshly varnished tubs packed in straw that had been taken from the paint shop in Manitowoc. And Chamberlain confirmed that the part of the ship that first went up in flames was exactly where this cargo was placed.

Horrified by the disaster, Albert Goodrich immediately ordered all the coal stoves on his ships removed, thereby removing the chance of another accident involving live coals. Instead his vessels would henceforth be heated by steam pipes. Goodrich also stated that the Seabird crew did not immediately stop the engines and man the lifeboats, as they had been ordered to do if fire ever broke out. And considering Chamberlain’s account of Captain Morris giving no orders to help save the passengers, it seems clear that gross incompetence played a role in so many lives being lost. As for the financial cost, the Seabird had been valued at over $50,000. Unfortunately, she was uninsured.

Paddle Wheel of the Seabird on the Bottom of Lake Michigan

photo: keng at DiveBuddy.com

Only one body was ever recovered from the lake, although a charred portion of a paddle box washed up on the beach south of Waukegan. The Sea Bird was painted along one side of it. Everyone agreed that at least twenty people might have survived had they only climbed onto the paddle box. It was a poignant reminder of how quickly things got out of control on the doomed ship.

While the exact number of people who were on board vary, at least one hundred burned to death on board or drowned in the rough waters. The Seabird disaster remains the sixth greatest loss of life due to fire on Lake Michigan.

---Sharon Pisacreta, March 2012

Resources for the Seabird:

Websites

The Seabird: An Historical Essay by Robert C. Gadbois

Burning of a Steamboat, New York Times, April 10, 1868.

Books

Great Lakes Shipwrecks & Survivals by William Ratigan. William B. Eerdmans 1960. Paperback

Lost Passenger Steamships of Lake Michigan by Ted St. Mane. The History Press 2010. Paperback