Back In The Day:

Saugatuck’s Dance Pavilion

Before and after the turn of the 20th century, entertainment for families consisted of picnics, circuses, carnivals, brass band concerts, vaudeville, small amusement parks and mineral bath resorts. Situated close by the Kalamazoo River’s northern banks, Saugatuck was a popular summer resort for wealthy and upper middle-class people from Chicago, St. Louis and other cities.

photo: www.memoirshop.com

Only the very rich could afford an automobile, although Henry Ford’s Model T was growing in popularity. Most people still traveled by train and steamship. Women and children rented cabins or stayed at hotels or boardinghouses for the summer, a month or just a week. Some working husbands only visited on weekends.

photo: fast-autos.net photo: www.memoirshop.com

Families would fish from the docks or rent canoes to explore the river, climb the sand dunes or two-hundred-plus stairs to the top of Mount Baldhead. They could rent a horse-drawn taxi that would take them to Oval Beach for a swim in Lake Michigan. The local photographer had a donkey for posing on the beach, and would sell the postcards as a memento.

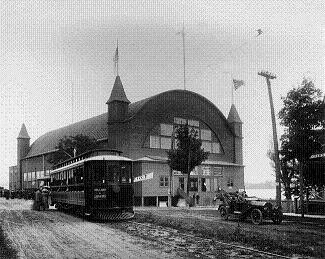

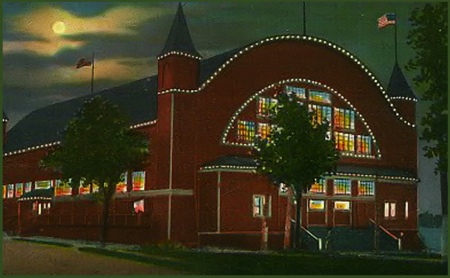

Saugatuck and Douglas businessmen, hoping to cash in on the popularity of the 1904 dance pavilion in South Haven, decided to build the largest venue in the Midwest. They formed the Saugatuck Amusement Company and purchased dockside property just south of Leindecker’s Inn (later the Hotel Saugatuck, and now part of Coral Gables). They hoped to open in 1906, but poor economic conditions delayed the project until spring of 1909.

One “promoter” of dance pavilions was Frederick Limouze, an investor from California, who had helped finance the South Haven pavilion and planned to back a project in Chicago as well. Elmer Weed, owner of the Douglas basket factory, and Saugatuck’s real estate businessman D. F. Ludwig became partners.

Work began on Saugatuck’s Pavilion in late April, with a deadline of the Fourth of July holiday for its grand opening. Over 300,000 board feet of lumber arrived on huge barges. Pilings had been driven to support a new dock, and a concrete surface of 200 feet by 105 feet was laid down. Workmen assembled the steel arches that would stand 68 feet tall, raised and bolted them into place.

PAVILION STRUTS

photo: http://198.110.177.200/SDpictures/viewpic.php?images/PavillionStruts

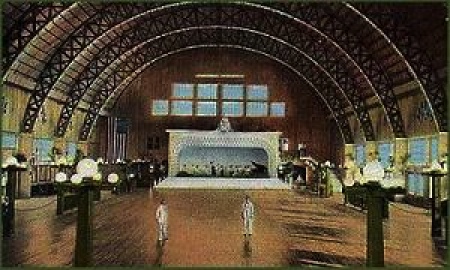

Carpenters finished the walls with siding, with the main entrance facing north and special arched windows above it, plus windows on each side. After four corner turrets were added, the entire outside was painted barn red. Workers finished an interior vestibule of 38 by 16 feet and laid a special dance floor of 100 by 60 feet. A bandstand for the orchestra was added as well.

Despite the village not having electricity, a generator was built to power the 10,000 electric lights. Half were strung along the exterior arches, sides and corner turrets, and could be seen by ships at night steaming across Lake Michigan. The red, blue, green, amber and white interior lights blinked on and off depending on the music’s timing, corresponding to a more lively two step or a sedate waltz.

PAVILION DANCE FLOOR

photo: Saugatuck Douglas Historical Museum

Although crowds remained large throughout the first summer until the pavilion closed on Labor Day, creditors could not be paid due to $25,000 in debts from the mortgage and building costs. The Pavilion still opened the following year, with an eye on maximizing profits. Everyone, dancers and watchers alike, paid admission and “dance tickets” were sold at eight cents each or seven tickets for 50 cents.

SCALE MODEL OF THE PAVILION

photo: sdhistoricalsociety.org

To maintain protocol, young men wishing to meet unescorted young ladies had to ask the Master of Ceremonies for a proper introduction. Refreshments of ice cream, popcorn, soda or lemonade were also sold—Saugatuck being part of the “dry” Allegan County. Young men who couldn’t afford the admission price tried to climb the lakeside balcony or the supports of the Pavilion’s south side. Once management discovered this, they placed chicken wire as a deterrent. On Sundays, concerts were held instead of dances with singers, musicians or the orchestra providing the entertainment.

By 1913, the Pavilion added a motion picture house presenting shows during the week. Community events were held at the pavilion: picnic dinners served by church ladies, piano recitals and dance lessons. Special dances were held at times, similar to musical chairs, where dancers would wait for the orchestra to stop playing and rush to stand on numbers painted in a row in front of the bandstand. Other times prizes were given out to the dancer lucky enough to stand on a certain number. A confetti battle even took place, with the women on the west side of the dance floor triumphing over the men on the east. ‘Farm and Barn’ parties, with prizes for costumes, beauty contests and dance contests were also held.

PAVILION INTERIOR

photo: http://www.memoirshop.com/Allegan/Saugatuck/Pavilion.html

The Barbino Orchestra from Chicago arrived in 1916, which raised the Pavilion’s popularity. Once America became involved in World War I, however, the number of orchestra musicians was severely reduced. “Over There” was shown on the Fourth of July in the movie theater. During some cold winters, several Great Lakes passenger ships stored gear and furniture inside the Pavilion for a fee. Insurance companies soon ended that idea in the early 1920s after a huge hotel fire in Holland. With so many structures made primarily out of wood, the chances of a fire spreading were too great.

photo: Saugatuck Douglas Historical Museum

A dress code remained in place, even during the hottest days of summer, with gentlemen keeping their coats buttoned except for special “shirtwaist” dances. Movies were screened for “clean” entertainment to avoid any vulgar influence on young people’s minds. Due to rising film costs, prices rose from 17 to 22 cents admission. By the end of the twenties, when flappers and jazz became popular, the Pavilion management introduced a radio station. By 1930, the movie theater installed a sound system to accomodate the change from silent movies to “talkies.”

The Depression years hit everyone hard. Instead of one orchestra, the Pavilion hosted a succession of bands and orchestras to keep crowds coming. Special events also helped, with various contests or souvenirs of parasols or noisemakers, and themed events such as Ireland Night or Mardi Gras Night. On Lindbergh Night, 2,000 toy airplanes were released from the Pavilion’s dome.

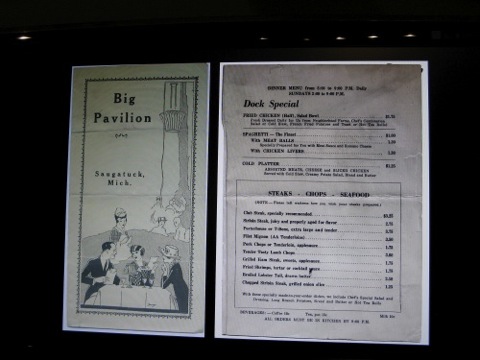

PAVILION MENU: Saugatuck Douglas Historical Museum

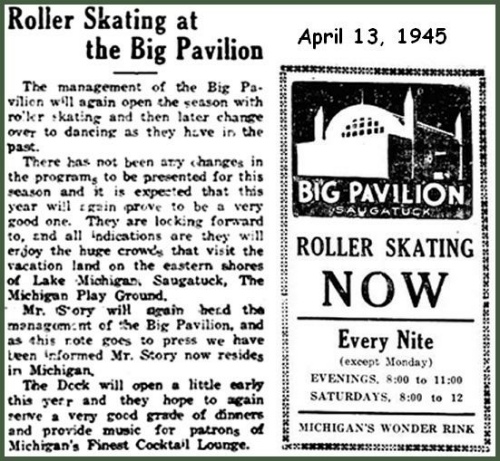

In 1938, “The Dock” restaurant opened in the Pavilion’s lower level, boasting a liquor license and “charcoal broiled” dinners. It became the “posh” spot in the village with a great view of the docks and yachts visiting Saugatuck. In order to extend the season, management installed a new maple floor and temporary pipe railing for roller skating. Skates could be rented, the old clamp-on style with straps, and ‘skate boys’ used shoeshine boxes to help patrons...for a dime tip.

.

photo: www.memoirshop.com

Those wanting to try stunts used the rink’s center, if any lessons were not in progress. Race competitions were also held. Diners downstairs in The Dock could hear the roaring noise above their heads. During and after World War II, the pavilion and its lower level restaurant became a place of true camaraderie with locals and frequent visitors alike.

The early 1950s, however, brought flood to The Dock and liquor license wars for it and the Pavilion. The restaurant had to be moved to the ground level, on the village side, with annexes for a kitchen, garage and storage. The Pavilion’s movie theater remained popular. Improvements included seats for 700 people and a Cinemascope screen. Dancing, however, had been reduced from every night to only weekends. The Saugatuck Association hosted wrestling matches, talent contests, fund-raising dinners, bazaars, antique shows, skating and card parties. The First Annual Saugatuck Jazz Festival in 1959 brought in Dizzy Gillespie and his band.

photo: sdhistoricalsociety.org

Since the Pavilion had long been showing its age, the Chicago owner finally decided to hire painters to prepare for opening in the spring of 1960. On May 6th, around noon, residents across the Kalamazoo River saw smoke rising from the Pavilion. By the time the fire department arrived with their equipment, flames had engulfed the Pavilion. Douglas’ fire department arrived to help, along with trucks from the surrounding towns including Allegan, Fennville, Holland and South Haven.

photo: www.memoirshop.com

Within one hour, the wooden building’s roof caved in and the firemen frantically tried to keep the fire from spreading to the village. The wind shifted southeast, although embers threatened some cottages across the water. The Saugatuck school principal bussed older students over the bridge to stamp out any small fires in the slopes and hills. Only one cottage burned. The Hotel Saugatuck (now Coral Gables) had a few broken windows and blistered paint. Most attributed the fire’s cause to a short in the wiring, and an investigation into arson was inconclusive.

Once the debris was cleared -- including four pianos, 400 pairs of skates, melted steel, glass from thousands of broken bulbs -- the owner and the Village Council sparred over rebuilding. Eventually, a parking lot was constructed. You can currently see the site in Saugatuck, just past the Village Hall near the curve of Water Street.

---Meg Mims, © Feb. 2011

Meg Mims features the Kalamazoo River Point lighthouse and Saugatuck's Dance Pavilion in her mystery FIRE POINT. Artist Sydney Sinclair, visiting the summer resort of Saugatuck, Michigan, finds the half-burned, strangled female keeper at the lighthouse. Sydney draws a sketch from a plaster death mask to help verify the woman's identity, but her efforts prove the victim is not the keeper after all. Sydney faces betrayal from friends and uncovers village secrets that lead to a second murder -- and sets her directly in the killer's path.

Contact Meg for more information at megmims@gmail.com or visit her website www.megmims.com

Sources for article:

Saugatuck’s Big Pavilion. Kit Lane. The Commercial Record, 1977.

Saugatuck/Douglas Historical Society: Society Publications

MemoirShop: The Big Pavilion

A Short History of Saugatuck

Feb '11 - Mar '11