Lighting The Lake:

The Beaver Island Lights

Beaver Island Head Lightphoto: Michigan Archives

Beaver Island emerged out of the glacier ice of northern Lake Michigan eleven thousand years ago. For several thousand years, it was actually connected to Michigan’s mainland due to low lake levels. When the waters rose, much of the land was again submerged, and it became the largest of several islands now known as the Beaver Island archipelago. Located approximately thirty miles offshore from Charlevoix, Michigan, Beaver Island stands at the western entrance to the Straits of Mackinac. Fur, fish and lumber have long been integral parts of this remote island’s economy. As early as the 1830s, islanders began to demand a lighthouse in order to keep their harbors safe and viable.

Beaver Island’s first lighthouse was constructed due to the hazards of navigating the shoals that lay just beyond the southern tip of the island. Sailors needed some sort of marker to let them know where Gray’s Reef Passage’s western edge was located as they traveled en route from the Straits of Mackinac to Wisconsin. Congress investigated the situation in 1838, and it was decided that a lighthouse should indeed be built on the island. Bureaucratic red tape stalled matters however, and Congress did not appropriate funds for construction of a light station until 1850.

Beaver Island Head Light

The new lighthouse was built on a 158-acre parcel of land on Cheyenne Point, a bluff at the southern end of the island. The brick tower of Beaver Island Head Light stood 46 feet high, and had an octagonal iron lantern. Fourteen Lewis lamps with reflectors provided illumination, while a covered passage connected the tower to the lighthouse keeper’s house. Construction of the station was completed in early winter of 1851, and the light was first lit at the end of that maritime season.

Unfortunately, much of the station had to be rebuilt in 1858. When bids were initially taken for the building of the light station, the lowest bid was accepted. This resulted in the use of sub-par building materials and shoddy workmanship. Reconstruction led to the replacement of the Lewis lamps with the superior revolving fourth order Fresnel lens. This new white light flashed every 90 seconds, and could be seen as far as 16 miles out on the lake in clear weather. A two-story yellow brick lighthouse keeper’s house was built in 1866.

Beaver Island Head Light

One of Beaver Island’s more colorful characters was Harrison ‘Tip’ Miller, who was appointed lighthouse keeper in 1863. Miller’s father brought the family to Beaver Island to follow the radical Mormon Prophet James Jesse Strang. Strang had proclaimed himself King of Beaver Island, and he ‘reigned’ over his subjects for six years until he was assassinated in 1856. Ironically, Strang also lobbied for lighthouses to be built on the island, primarily because he wanted to make it easier for ships to put into port in order to buy his cordwood. After Strang’s death, things returned to normal for the islanders, and ‘Tip’ Miller went on to enjoy a long and productive life.

While keeping the light, Miller also worked as a fisherman, mail carrier, cooper and businessman. In addition, he and his Irish wife raised their ten children in the yellow lighthouse keeper’s dwelling. In 1887, he was transferred to the Life Saving Station at Point Betsie but during his tenure at Beaver Island, Miller and his crew undertook a number of celebrated maritime rescues. After 21 years of service at Point Betsie, Miller at last retired and in 1908 returned home with his wife to Beaver Island.

As shipping traffic increased between Beaver Island and North Fox Island, a fog signal building became necessary. This new building was located 650 feet west of the lighthouse on Beaver Island. On December 6, 1890, the first 7-second blast of the new fog signal was officially sounded; its steam fog siren was transferred from Skillagee Light Station. The lighthouse keeper and his assistant already had enough duties keeping the light, so another assistant keeper was dispatched to Beaver Island to help carry the workload of the fog signal building. This also necessitated enlarging the lighthouse keeper’s house.

Whiskey Point Light

It wasn’t only the southern tip of Beaver Island that required a lighthouse, and the north has its own story of how they came to have a light station. The first white settlement on Beaver Island was Whiskey Point. Established in 1839, the trading post dealt largely in fur and whiskey. At this time, the island’s Paradise Bay became the economic hub of northwest Michigan, replacing Mackinac Island. St. James’ natural harbor in Paradise Bay soon attracted the maritime traffic of the Great Lakes, and ships traveling between Chicago and Buffalo made regular refueling stops here. And when one of Lake Michigan’s many fierce storms struck, the harbor became a frequent safe haven for sailors.

Drawn by this increased traffic, the fishing and sawmill industries soon became regular visitors to the harbor. But along with the geographic advantages of Paradise Bay, sailors also had to deal with unpredictable and hazardous weather, especially the thick fog that often blanketed Lake Michigan. A second lighthouse was therefore commissioned for Beaver Island.

Whiskey Point Light

Construction on Beaver Island’s Harbor Light was completed in 1856. Located at the northern end of Beaver Island close to St. James Township, the lighthouse is sometimes referred to as Whiskey Point Light or St. James Light. However problems arose with the first building; it was deemed to be too small and its mortar defective. As shipments of lumber increased from the western ports to the Manitou Passage, the Lighthouse Board advised a larger light be built to better facilitate the harbor’s status as a shipping hub. The lumber barons of Michigan exerted pressure on Congress, resulting in a $5000 appropriation for construction of a new station.

In 1870, construction began on a new station at Harbor Light. A taller 41-foot round tower was erected along with a story and a half keeper’s house, all made of Cream City Brick. A ten-sided cast-iron lantern boasted a new red Fourth Order Fresnel lens. Although the lighthouse was in a hard to reach location, it was not until the 20th century that a road was built connecting it to the town of St. James.

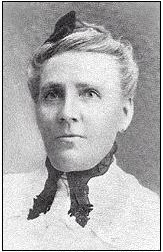

Elizabeth Whitney Van Riper Williams

President McKinley’s nephew reputedly was the second keeper appointed. He was succeeded in turn by Clement Van Riper. During his tenure as keeper, Van Riper fell ill and his wife Elizabeth Whitney took over many of his duties. After Van Riper died trying to rescue the crew of the distressed Thomas Howland, his widow officially became the next keeper of Harbor Light. This was no small task for a woman alone whose duties included keeping a lard oil-fired lamp burning under the worst weather conditions. Indeed she worked as the sole lighthouse keeper for three years, before marrying Daniel Williams in 1875. Elizabeth continued on as keeper at St. James Harbor Light until 1884 when she asked to be transferred to the new lighthouse at Little Traverse Point. Elizabeth kept the light at this new lighthouse on the mainland for 29 years until her death in 1913. By that time, she had become a celebrated and beloved figure at Little Traverse Bay, having spent 41 years keeping the light on the Great Lakes.

Emil Winter was the last keeper of Harbor Light, and remained in residence with his family even after the light became automated in 1927. The keeper’s dwelling was taken down during WWII. However the light is still in use and serves as a beacon for the Beaver Island ferry.

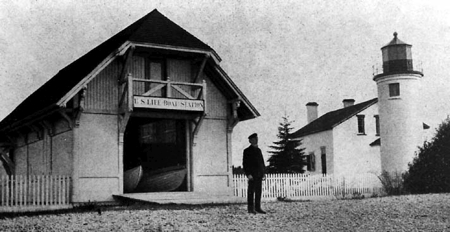

Beaver Island Light and Life Saving Station

Sailors did not have to rely only on the Beaver Island’s lighthouses and their keepers for safe passage. Before the existence of the Coast Guard, maritime rescues were the responsibility of the Life Saving Service created by Congress in 1874. The first life saving station in Michigan was established on Beaver Island at the site of the old trading post at Whiskey Point. The Life Saving Service volunteers were paid $10 for every life they saved. Responding to the sound of a whistle, these islanders would head for their small boats and brave whatever gale storm had caused the emergency. While untrained, these men were long-time sailors and fishermen and protected ships in distress in the Bear Island archipelago from South Fox to north of Garden. Such was their bravery and skill, that from 1875 to 1900, not a single life was lost during their rescues.

US Life Saving Service

The Coast Guard was created in 1915 as a result of the Life Saving Service merging with other rescue organizations. In the first half of the 20th century, the Coast Guard became a regular presence on Beaver Island, prompting island residents to enlist as members of their manned crews. The Lighthouse Service became part of the Coast Guard in 1939, expanding the Coast Guard’s range to the Lansing Shoals, Gray’s Reef and North Manitou Island.

A look-out station was erected by the Coast Guard at Sucker Point in order to watch the channel at Garden Island. Another duty that the Coast Guard undertook for Beaver Island residents was serving as their fire department. And finally, the Coast Guard Station “Island Phone” served as the Island’s emergency contact with the rest of the world. Beaver Head Lighthouse was finally decommissioned in 1962. The Charlevoix Public Schools took possession of it in 1975, after it spent several years as a hunting club. The lighthouses of Beaver Island are currently open to tourists and well worth the visit to this most remote island in Lake Michigan.

—Sharon Pisacreta, © December 2012

RESOURCES

Beaver Island Harbor Light at Terry Pepper's Seeing The Light website

Beaver Island Harbor Light at Wikipedia

Beaver Island Harbor Light at Beaver Beacon

St. James Harbor Light at Boatnerd.com

Beaver Island Head Light at Wikipedia

Beaver Island Head Light at Terry Pepper's Seeing The Light website

Women and the Lakes: Untold Great Lakes Maritime Tales