Lost to the Lake:

The Last Voyage of The Christmas Tree Ship

Of all the tales of ships lost to the lake, there is only one that involves a cargo of Christmas trees and the death of a man known as ‘Captain Santa’. The holiday nature of the ship’s crew and mission lends a special sadness to the story of the doomed Rouse Simmons, more commonly known as the Christmas Tree Ship.

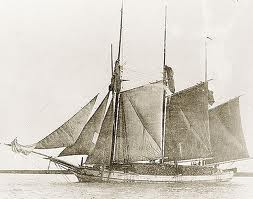

The Rouse Simmons was a three-masted schooner built in Milwaukee in 1868. Soon after construction, the schooner was purchased by Charles H. Hackley, a wealthy lumber owner from Muskegon. For twenty years, the Rouse Simmons transported lumber to various ports along Lake Michigan. But after its service in Hackley’s fleet, the Rouse Simmons became a “tramp ship” until Herman Schuenemann became a part owner in 1910.

Since 1896, Herman Schuenemann had been transporting Christmas trees to Chicago. However it was his older brother August (nicknamed ‘Christmas Tree Schuenemann’) who first began to deliver cargoes of evergreen trees to Chicago in 1876. Tragically, August was lost to the lake in 1898 when his own ship S. Thai sank in a November storm near Glencoe, Illinois. Ironically, August’s ship was also carrying Christmas trees when it went down.

Although devastated by his brother’s death, Herman continued in the family business, hauling Christmas trees from Michigan to Chicago via ship and selling them to city residents near the docks at the Clark Street Bridge. Because Herman sold directly to consumers, his prices were lower than his competitors, and his business was advertised as “Christmas Tree Ship: Our Prices are the Lowest”. A charitable man, Herman not only sold his trees for .50 to a dollar, he also donated many of his trees to the city’s needy families.

By the early 1900s, Herman Schuenemann was a popular fixture in the city. Whenever the Christmas Tree Ship docked in Chicago during the holiday season, crowds were eagerly waiting to board and choose their trees and garland. It was said that “the Christmas season didn’t arrive until the Christmas Tree Ship tied up at Clark Street.” And like his brother before him, Herman was given an affectionate nickname: ‘Captain Santa’. He even possessed a Santa-like personality: jolly, generous, and instantly likable.

In 1910 Herman decided to use the newly purchased Rouse Simmons to transport his Christmas trees. He decorated the schooner with electric lights and fastened an evergreen tree to the top of its mast. The schooner became an integral part of the Schuenemann family business, traveling every November from Chicago to Manistique in northern Michigan. Herman had earlier bought 240 acres in the Upper Peninsula where, hoping to further omit any middleman, he began growing his own trees. But even this did not prevent the business from experiencing serious financial difficulties.

In November 1912, Schuenemann docked in Manistique’s Thompson Harbor where he loaded the Rouse Simmons with 5,500 trees. Because of bad weather, his competitors had not made the weeklong trip from Chicago. However Schuenemann’s company was in financial trouble, and he urgently needed the profit that would result from the transport of these Christmas trees.

With his competitors out of commission – and snow blanketing tree farms along the shoreline - Schuenemann was convinced that delivering these trees would be his financial salvation. Indeed everything the Schuenemann family had was invested in this particular cargo.

The day the Rouse Simmons set sail, many ships refused to leave port due to 60 mph winds. One serious storm had already hit Lake Michigan that month, and conditions promised another bad storm on the way. Even some of Schuenemann's own crew refused to go, especially after seeing rats leave the ship which was taken to be a sign of bad luck.

But determined to haul as much cargo as possible, Schuenemann loaded the ship with thousands of trees. This put too much weight and stress on the 44 year-old schooner, especially when confronted by the gale winds of November. In addition, for several years now, it was suspected that the Rouse Simmons was no longer seaworthy.

Still, the Christmas Tree Ship set sail from Thompson Harbor at noon on November 22, 1912. A three hundred mile trip to Chicago lay ahead of them. That night, the ship was hit by a fierce winter blizzard and two sailors were swept overboard by the waves. These same waves also swept away some bundles of trees and a small boat, which mercifully lightened the schooner’s load. There are indications that Captain Herman Schuenemann decided to head for Bailey’s Harbor, but the winter storm was gaining strength. The battered ship was buffeted by hurricane force winds, and the cargo of thousands of wet trees became weighted down with ice.

On November 23 at 2:50pm, a surfman at The Life Saving Station in Kewaunee caught sight of the Rouse Simmons. Ominously the ship’s flag flew at half-mast, a sign that it was in peril. The ship’s flags were in tatters, and it was observed to be sailing dangerously low in the water. A power boat was sent out within the hour to try to effect a rescue, but heavy snow hampered visibility and the Rouse Simmons was never seen again. Tragically, the fierce storm also claimed three other ships before it was through. As for the Christmas Tree Ship, all eleven crew members, including ‘Captain Santa’, were lost.

Yet, that wasn’t the last the world heard from the Christmas Tree Ship. A bottle containing a message from the ship washed up along the Wisconsin shore at Sheboygan. Inside a message read: “Friday…everybody goodbye. I guess we are all through. Sea washed over our deck load Thursday. During the night the small boat washed overboard. Leaking bad. Ingvald and Steve fell overboard Thursday. God help us. Herman Schuenemann.”

The following spring, commercial fishermen were surprised to haul up nets weighted down with balsam and spruce trees. Then twelve years later, Schuenemann’s wallet – wrapped in oilskin -- also turned up in a fishing net. Finally, in 1971 a Milwaukee scuba diver Gordon Kent Bellrichard discovered the actual wreck of the Rouse Simmons lying 172 feet below the surface of the lake.

From aqua.wisc.edu

The wrecked ship still held many of its trees in the hold. Studies of the wreck also suggest that the Simmons had steerage capability almost to the end, and was sailing for a shelter or safe harbor right before it went down. The site of the wrecked ship is now part of the National Register of Historic Places; several items rescued from the ship can be found at the Milwaukee Yacht Club and the Rogers Street Fishing Village Museum in Two Rivers, Wisconsin.

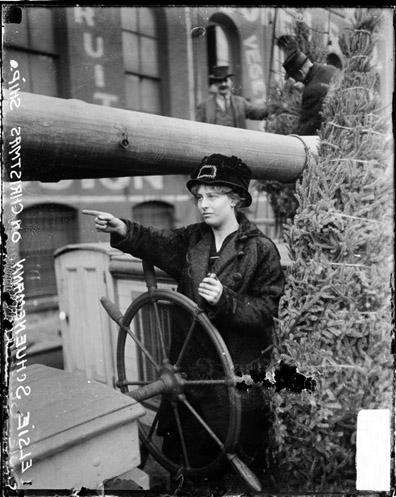

As for the Schuenemann family, they were determined to carry on their Christmas tree legacy. Despite the tragic loss of Herman, 1913 saw Mrs. Schuenemann and her daughters once again cutting down evergreen trees in Michigan, and delivering the cargo to Chicago.

Elsie, one of his daughters, took over the family business, running it for twenty years and garnering her own nickname ‘The Queen of Christmas Trees’. And for her generation, there were thankfully no more ships filled with trees that were lost at sea. Instead, her ships laden with evergreens continued to bring Christmas cheer to the children of Chicago. And when she eventually married in northern Michigan, she and her groom stood beside a large decorated Christmas tree…which she had just cut down.

---Sharon Pisacreta, © Dec. 2010

Resources for the Rouse Simmons:

The Christmas Tree Ship: Captain Herman E. Schuenemann and the Rouse Simmons by Glenn V. Longacre, The National Archives.gov, Winter 2006.

Lives and Legends of the Christmas Tree Ships by Frederick H. Neuschel, 2007.

Rouse Simmons: The Story of the Christmas Tree Ship by Joe Nowak, Nov. 2010.

The Christmas Tree Ship: The Story of Captain Santa by Rochelle Pennington, 2002.

The Historic Christmas Tree Ship: A True Story of Faith, Hope and Love by Rochelle Pennington, 2004.

Great Lakes Shipwrecks & Survivals by William Ratigan, 1960.

Dec '10 - Jan '11